Insights into Clinical Deep learning

Published:

=======================

Insights into Clinical Deep learning

Why is Deep Learning in Healthcare unique?

In this blog, I shall try to describe my observations of how deep learning is different in the medical domain. What’s different in healthcare.

First of all, lets get the few obvious ones out of the way – scarce datasets, lack of good data annotation, imbalanced datasets, lack of proper demographics representation(as per use-case population). These applies to deep learning in general.

In this article, we will look at special issues with AI in healthcare and emphasise that building, deploying AI in healthcare requires a lot more personalization and detail to attention. We will consider a few different examples from neuroimaging, histopathology, and drug discovery frameworks. While this is focused on healthcare, I hope some of this translates to other domains as well.

So let’s get started.

Data quality

The Source of data is important. In a study by Google health [A Human-Centered Evaluation of a Deep Learning System Deployed in Clinics for the Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy – https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376718%5D, authors found that several socio-environmental factors impacted the model performance, workflow, and the patient experience. Data is potentially the most common source of eventual bias in the final model. The best way to avoid such bias is generally, to get quality data from as varied geographies, sources, with enough confounding factors. At times, robust data augmentations are used to overcome the lack of data examples.

Data preprocessing

Unlike other domains, Medical imaging data generally requires a lot more preprocessing. A few examples in radiology space are –

- Windowing of scans

- Bias field correction

- Image registration – very common practice in medical imaging. To define it informally, it image registration aligns all misaligned data to a standard anatomy atlas for easier interpretation. There are several types of algorithms that allow us to do that.

- Size harmonization – Same physical definition of all images, things like fixing for slice thickness and slice numbers – Old CT/MRI scans have few slices(32) per scans, new ones now might have 200+ slices.

- Intensity harmonization: Same intensity profile, i.e., normalization [4, 5, 6, 7]. Z-scoring.

- Skull stripping – might be required in other cases.

For histopathology slides, we generally have a very huge slice of the scan, which can be broken into smaller segments beforehand.

For drug designing, one might need graph transformations(TargetNormalize, VirtualNode, RandomBFSOrder or Molecule transformtaion(RemapAtomType, VirtualAtom)

The bottom line is things are different from traditional deep learning.

Smart but not-overkill augmentations

The main idea of augmentation is to increase the data when you don’t have enough, or try to generate specific cases that might be seen in the real world, but are missing in your dataset. Things get blurry when one moves towards robust augmentations. If a model’s performance increases by augmentation it in a way that’s not intuitive to a clinician let’s say, it becomes hard to explain it. But, this works in improving the performance of the model more than often.

Image augmentations like normalization might hurt the image texture, something that is more than often relevant in medical images. You can check my paper summary below, of an amazing paper that talks about the same.

Synthetic datasets

With the rise of GANs, now we can generate synthetic datasets – Image or tabular. A lot of Kaggle competitions now are also hosted using synthetic datasets. There are websites like “This face doesn’t exist”, “This face doesn’t exist””This face doesn’t exist”. But, we haven’t reached a similar level for medical imaging yet. (latest as of 2021).

Medical imaging data is complex than most other imaging tasks. We are still at solving classification and segmentation problems. Also, one important area, where medical imaging differs from other imaging tasks is that, detection of disease generally depends on “texture-level” features, and not macro-level features in, let’s say cat vs dog classification. And since most synthetic data generation algorithms are deep down an encoder and decoder or generative and discriminator. At times, indications of findings are mild changes in texture or opacity. This might be the reason why explain-ability tools like GradCam might not always be helpful.

A funny way of saying this is – “We can’t draw, what we can see(imagine).” Hopefully, in the coming years, we will have more advanced algorithms or better ways to generate medical imaging data without losing disease findings.

That being said, doesn’t mean that we cant be creative.

ClinicaDL is the deep learning extension of Clinica, an open-source Python library for neuroimaging preprocessing and analysis. It provides 3 smart ways to do it.

- “Trivial” data is super easy synthetic datasets, that would very likely give a perfect score for the model. This can help us check for bugs in our frameworks, pipelines.

- Indissociable images – randomly generated and split images, create a dataset, that cant be classified at all.

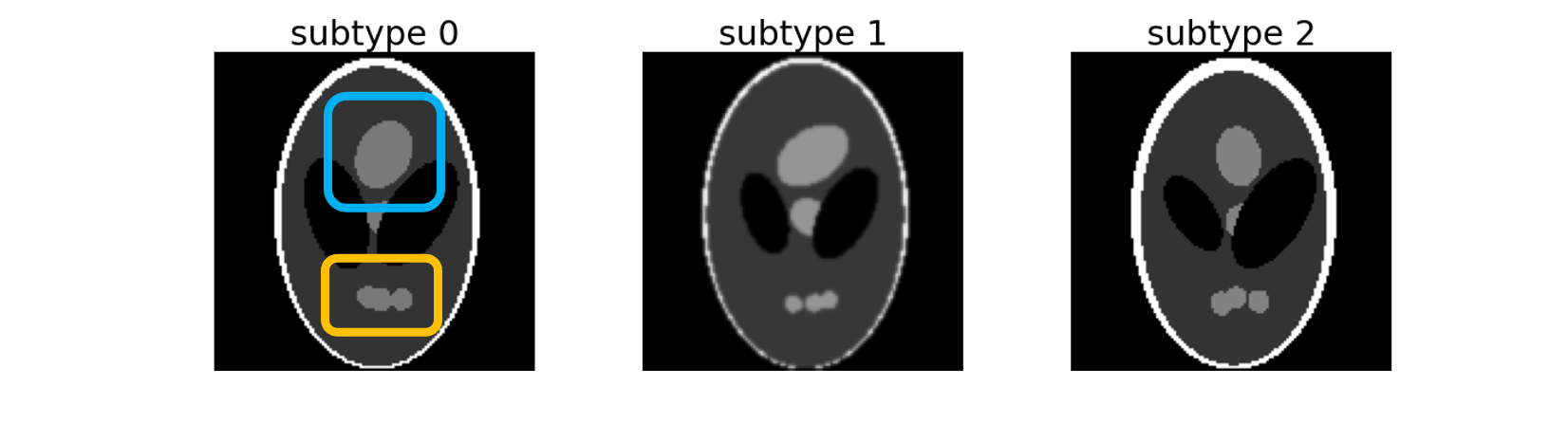

- Shepp-Logan phantom, a standard image to test image reconstruction algorithms, creates three sub-types of 2D images distributed between two labels. These three subtypes can be separated according to the Top (framed in blue) and Bottom (framed in orange) regions: – subtype 0: Top and Bottom regions are of maximum size, – subtype 1: Top region has its maximum size but Bottom is atrophied, – subtype 2: Bottom region has its maximum size but Top is atrophied.

Now, this can be seen as augmentation, but there might be some interesting use cases in quantification problems. This is also particularly important in the use case of Alzheimer’s disease, where findings vary in different.

Choosing model architecture

In general practice, we tend to choose the most recent model, that outperformed previous ones on the ImageNet dataset. There is growing evidence that models optimized for higher performance on the ImageNet dataset, might not be optimal for medical imaging tasks.

In the paper, the authors found out that previous models like DenseNet still performed better than newer architectures(like EfficientNet, SqueezeNet) for medical imaging datasets. Performance on ImageNet doesn’t necessarily translate to performance on medical datasets. You can read my summary for this paper, here.

Link to the paper – https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.06871v2

k-Folding vs Multi-cohort training

Clinical-DL allows you to train models in a “Multi-cohort” and “Multi-network” manner. Normally, entire images are used as input of a unique network. With Multi-network, a network is trained per image part(One model per ROI mode). Multi-cohort allows you to train the model in cohorts, similar to what we very commonly use in K-fold or stratified-K-fold learning.

Ensembling Image-level results

3D CNNs are what come to mind when thinking of 3d data like CT scans and MRI. The problem with 3D-CNNs is the dimensionality curse, different number of slices in each 3d scan. This makes it difficult to train a model for such cases.

Several approaches might use several models for specific parts of images, and later ensemble the results together. This can be done for each slice in case of 3D scans, a part of 3D MRI volume, or every ROI in segmentation cases.

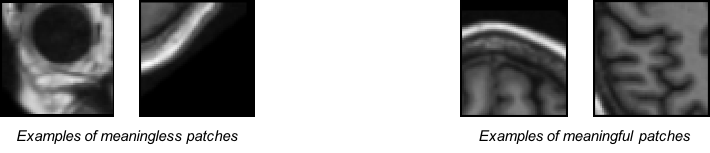

For classification or regression tasks that take as input a part of the MRI volume (patch, ROI, or slice), an ensemble operation is needed to obtain the label at the image level. For the classification task, soft-voting was implemented as all inputs are not equally meaningful. For example, patches that are in the corners of the image are mainly composed of background and skull and may be misleading, whereas patches within the brain may be more useful. For the regression task, hard-voting is used, then the value of the output at the image level is simply the average of the values of all image parts.

Reference – https://clinicadl.readthedocs.io/en/stable/Train/Details/#image-level-results

Reasoning, Uncertanity and Confidence interval

Knowing the uncertainty in the model’s prediction is important. That’s true for any AI. But in Medical AI, wrong decisions have a high cost. Not only would a physician want to know why the model thinks the decision it is showing, but one also needs to know the uncertainty in the predictions.

Artificial Intelligence and Human Trust in Healthcare: Focus on Clinicians – https://dx.doi.org/10.2196%2F15154

The neurons in the output layer provide a prediction probability for the output. That means little for clinical interpretation. In the paper, Analyzing the Role of Model Uncertainty for Electronic Health Records (https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.03842), the authors show that population-level metrics, such as AUC-PR, AUC-ROC, log-likelihood, and calibration error, do not capture model uncertainty. Physicians often look for confidence intervals around the predicted value. Changing seed value can result in different results even for well-optimized models.

Gradient Backprop, GradCAM, SHAP values, XIA, and several other approaches have been developed. These allow us to understand areas of interest to the model while making the prediction.

GradCAM++ for Classification, 2D segmentation, 3D segmentation scans Source – https://github.com/MECLabTUDA/M3d-Cam

Adoption and deployment of digital tools in healthcare

factors impacting clinicians’ adaptation of mobile health – https://doi.org/10.2196/18072

Healthcare is different in the way it operates, the amount of regulation, budget deficits, inter-dependence between healthcare organizations make it challenging to create a universally friendly and economic product. data privacy, perceived usefulness of “Automation tools” adds to the problem as well. Several studies found that clinicians often believe that using technology will interfere with their ability to make independent decisions. [https://dx.doi.org/10.2196%2F11072]

Mobile apps cant be used as plug-and-play for medical imaging. Medical images generally have very specific file formats and custom libraries to read them. Just capturing images from a camera, doesn’t help the use case. While quality data is scarce in medical imaging, most of what we have is in DICOM/NIFTI formats. This may require preprocessing, part of which is discussed later in this blog. The model would require more than just tweaking to be able to use camera-captured chest x-rays.

This reduces the ease of deployment of such algorithms. In the paper, Recalibration of deep learning models for abnormality detection in a smartphone-captured chest radiograph, the authors discuss a recalibration method to build deep learning models to detect radiological findings from mobile photographs.

Testing your models – Measure what’s clinically important

Most deep learning research papers assess diagnostic accuracy in a way that doesn’t reflect clinical practice. Mostly, while evaluating these algorithms against healthcare professionals, many cases are excluded at screening and very few of the included studies reported comparisons with healthcare professionals using the same test dataset. Recently, we are seeing the rise of reader studies to see the effect of deep learning algorithms in real clinical practice. External validation is always important. In a review paper ( https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30123-2 ) authors found that most studies undertake an out-of-sample validation for the model, but not for both either healthcare professionals or deep learning algorithms.

Looking into model outputs, wrong predictions(False positives and False negatives), distribution of prediction probabilities is some of the musts.

The model should also be evaluated for performance in the presence of confounding factors and desired target population.

Complex data structure

Healthcare data isn’t ways structured. The structure of physiological data is irregular and unordered. This makes it hard for us to make a matrix out of it. This applies to other domains as well – chemistry, drug design, genetics, where the data cant be represented be necessarily represented as a vector and requires more complex data structures. This is where Graph neural networks can help. Graph neural networks can capture relationships between diff entities, where each entity/node can be any feature. For example, every slice feature can be represented as a node of a graph, and also account for time series (Spatio-temporal GCNs).

Reach out to me –

I would love to hear your thoughts on challenges you find in deep learning in general and your domain-specific challenges. Please leave comments below about your thoughts on this. I would love to chat with you about this. You can find my email in the about me section.

More interesting reads-

- Minimum information about clinical artificial intelligence modeling: the MI-CLAIM checklist – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-1041-y

- Critical Appraisal and Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews of Prediction Modelling Studies: The CHARMS Checklist – https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001744

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement – https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- A review of deep learning in medical imaging: Imaging traits, technology trends, case studies with progress highlights, and future promises – https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.09104

- Understanding Clinicians’ Adoption of Mobile Health Tools: A Qualitative Review of the Most Used Frameworks – https://doi.org/10.2196/18072